-

I used to find dead insects in your pockets

Sewing, Keep Care, 2019

“Collaborate: to work with someone else for a special purpose”.1

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, assembles a fluid archive of objects that are connecting devices in my relationships. These objects; ferns, curtains, containers and the things within them, such as hair, shells, insects, are gathered, cared for or re-created by me, forming a kind of catalogue of traces which connect me to my past. They are also a medium for moving forward. Relationships are enacted, memories are conjured up in the process of handling, organising and being with them, shifting through time together. Boundaries of lived experience and fragments of memory become blurred, it is as though I am collaborating with my Nana while I work with my children, that we stand here together at the same moment in time.

My interest lies in the power such images as objects have in forming identities, the stories one may foreground in response to a visual, text, or oral archive. These responses also seem to connect and reinforce social bonds, where I work back and forward with my Nana and my children, within my network of friends. These objects become part of our vernacular exchange.

Working, install at home, I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2019

Maureen Lander’s Flat-Pack Whakapapa, a touring exhibition from 2017 – 2019 explores connections between whakapapa or genealogy and raranga, flax weaving.2 Coming from mātauranga Māori, a Māori world view, Lander plays with a contemporary understanding of relationships. Where family, kinship and networks are mobile, shifting and expanding across time. The work consists of installations of woven objects that can be added to, packed down, and reinstalled in each gallery space. The result of an ever expanding collaboration, the woven objects have been created by various groups, via workshops and under Lander’s guidance. The act of collaboration extends the life of the work, the potential is for the project to be ongoing, connecting and reconnecting with each new iteration of Flat-Pack Whakapapa.

Lander designed the project, providing instruction in the form of workshops, then outsourcing the making of the work to other weavers. Then Lander, in turn drew all the work of many hands together in an installation. During an interview with Priscilla Pitts at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Lander places value on relationships, stating that is what interests her. This may be relationships with her materials, her whanau and the various communities she engages to work with her.3 This seems to add a durational quality to the work, not only in the process of making and installing each new iteration of the work, but that these relationships do not necessarily end when the project ends. In Flat-Pack Whakapapa there is the sense that the dialogue continues, some of the connections formed may be strengthened, while others may well slip away.

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2019, detail.

The objects in I used to find dead insects in your pockets are quite ordinary. They speak to the everyday routines, everyday needs and activities of a household for example, the blankets in Keep Care. Despite their vernacular language, they seem extraordinary to me as they relate to the work of care and attention to the needs of family, and the memories that I call up with these objects. Opening up long closed cupboards and deep drawers led to the discovery of eleven blankets that my nana had made in the 60s and 70s for the beds in her home and in a family bach. She had given me one, years ago, and there was one on my bed whenever I stayed with Nana and Poppa, so I knew of these blankets. I didn’t realise she had made so many, and I can feel the work in them, the weight of them. They are the embodiment of care of my family history, they have been on the beds of other members of my family, they will have felt the weight and warmth of these objects. On close inspection, most of the blankets are marked and stained, some with holes, one has been seriously damaged by sunlight. This reveals something of the lives they’ve lead.

The domestic interior is often a location where these relationships play out. Relationships that happen within this space and the stories that can be told through these everyday objects inform the dialogue I wish to foreground in I used to find dead insects in your pockets.

I also see tangible, but invisible work; the maintenance, that Mierle Laderman-Ukeles focuses on in her performance work:

clean your desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor, wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the fence, keep the customer happy, throw out the stinking garbage, watch out don’t put things in your nose, what shall I wear, I have no sox, pay your bills, don’t litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets, go to the store, I’m out of perfume, say it again—he doesn’t understand, seal it again—it leaks, go to work, this art is dusty, clear the table, call him again, flush the toilet, stay young.4

The relationships I have with the objects are specific to members of my family and circles of kinship. The original fern in this installation was cared for by my mother and now lives with me, my children and our friends. The fern is a stand in for our connections to one another, we share the care of and live with them, collaborating with tips and knowledge and regular care of the plant;

they are not as sensitive as you think, just keep them moist, give them a sunny aspect, but out of direct sunlight.

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2019, studio detail.

Working with my Nanas shells, and those collected with my children, I collaborate with Nana and my children on a shared project, the outcome of which is still a mystery, but a part of our everyday lives.

Is this way of working, a model of collaboration and exchange, that can exist in the physical absence of another person? Creative practice often involves working with, or from existing research and ideas. The body is present even if in disguise: Tracing the Trace in the Artwork of Nancy Spero and Ana Mendieta, charts a body of work I consider an unconventional, collaborative social project.5 The conversation between the artists appears to exist across time, and despite Mendieta’s death, I interpret it as an exchange. It is also unusual in that the homage is made by an older artist in response to the work of a younger artist. This is a reversal of the usual ways that artists relate to one another, based on the patriarchal hierarchy of mentor/student dynamic.

Mendieta’s performance, Body Tracks (Rasrtos Corporales) 1982, was described as an intimate event, with a small audience that consisted of the New York art community, including Spero, who were given minimal information about what would happen.6 The audience was positioned facing three large, blank pieces of paper in a softly lit space. Accompanied by the sound of beating drums Mendieta dressed in plain clothes, entered the room, dipped her arms into a bowl of animal blood and tempera, her hands thoroughly coated in the pigment, she stepped up to a sheet of paper, pressing her hands and arms against it. Mendieta dragged her hands and arms down, leaving behind blood red streaks which still held the hand-print trace, this process was repeated two more times, leaving a series of drawings on the wall for the audience to view, after which Mendieta walked out of the room, leaving the audience with the drawings.7 Spero made a series of works in response to this performance, described as “…re-tracing, re-presenting and re-telling.”8 These works incorporated the image of the handprint and text, one work, The Ballad of Marie Sanders, The Jew’s Whore, included a spontaneous action that became an homage to Mendieta’s Body Tracks (Rasrtos Corporales) performance.9

Spero was present at Mendieta’s performance of Body Tracks (Rasrtos Corporales), and her work in response continues the dialogue, even after Mendieta’s death. In a similar process, painter Kirsten Carlin regards working with a series of Francis Hodgkins paintings to be a kind of social practice, connecting Carlin with Hodgkins across time.10 This relationship forms as Carlin studies Hodgkin’s visual language, process and content. Then by finally producing a collection of paintings in response, bringing Hodgkins work into a conversation with the contemporary field of painting. It is a similar kind of exchange or conversation when I work with and re-create objects in I used to find dead insects in your pockets. Revisiting memories and places, I learn more about the people I’m working with. This may result in new understandings, re-establishing those bonds when I re-perform actions with people in my life now, like the dead dragonfly my daughter brought me.

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2019, Luna’s dragonfly, detail.

Notes:

1. Collaborate, Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary.

2. Pitts, ‘Maureen Lander’.

3. ibid.

4. Ukeles, Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!

5. Walker, The Body Is Present Even If in Disguise.

6. ibid.

7. ibid.

8. ibid.

9. ibid.

10. Carlin, Kirsten. Navigating Art Contexts.

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2019, detail.

-

Golden Oyster, not a true oyster

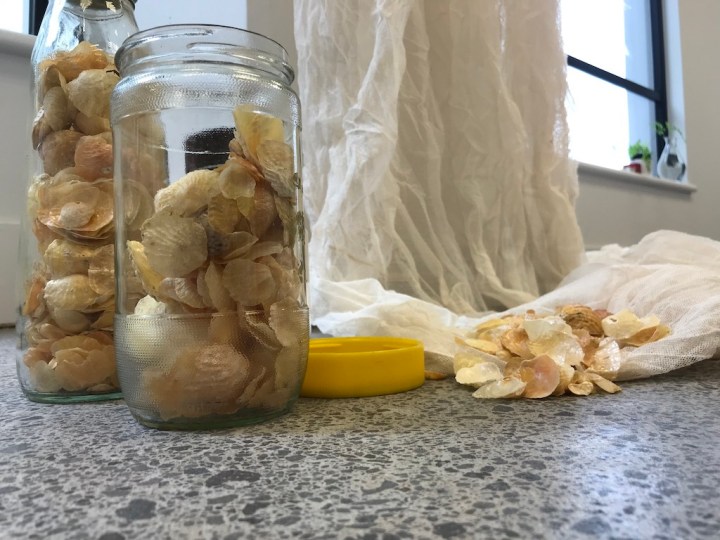

Golden Oyster, Anomia trigonopsis 51-83 mm.

The golden oyster is an irregular, oval shell with different valves. The convex upper valve is wrinkled, shiny and deep gold to slivery white. The thin, translucent lower valve grows to fit the contours of the underlying rock or shell. The upper valve develops the same sculpture because during growth the two valve margins fit together. Some lower valves are bright green. The hardened byssal plug emerges through a large hole near the hinge to secure the golden oyster onto the rock or shell.1

I used to find dead insects in your pockets, 2020, installation detail.

Nana and I would walk the beach; not far from her house, looking for these shells, each time I found one of the ‘right’ shells, I would feel a sense of satisfaction. She was clear about what she wanted, while she loved many shells, these were The Best. Golden, thin and fragile, what we were collecting them for, I will never know. Going back now, to these beaches with my children, I don’t find these shells. The coast has changed with the expanding city and housing developments. Our collecting may have contributed to this loss, or conversely it may also performed a preservative role. Those places and moments now exist in her jars, which I keep care of (Fig. 1). 1 Morley, Margaret S. Photographic Guide to Seashells of New Zealand, (page 39). -

Lockdown portraits; I’m sad because I miss you, and I don’t know when I’ll see you again

Lockdown portraits; I’m sad because I miss you, and I don’t know when I’ll see you again.

In response to the practical realities of Lockdown level 4 in Aotearoa, I considered my closest relationships, those that, of necessity that I need to care for, and those that I most wish to care for. The people I see everyday, my children and those in my somewhat extensive ‘bubble’, and those I love, who would now become long distance relationships for an unknown period of time.

After skirting close to self portraits during my MFA I began a series of self portraits, drawing on images I have shared with my intimate connections, Lockdown portraits; I’m sad because I miss you, and I don’t know when I’ll see you again, a series of selfies stitched in to cloth.

This process brings images, as traces of relationships into the ‘real world’, making this long distance relationship feel more tangible.

-

Lockdown walks; uncontrolled environments

Let them eat cake

During Lockdown Level 4, I engaged in a kind of government sanctioned photographic project. Lockdown walks; uncontrolled environments, involved gathering and sharing images taken on long walks, this has become a creative ritual, as I posted the images to instagram.

Wild flowers

Under lockdown in Aotearoa, walking in one’s local neighbourhood is permitted for health and wellbeing. Four days each week I walk alone, starting from my suburban home, these walks are up to 2 and half hours and range between 10-12km, within this time and distance I can traverse both rural and urban landscapes.

Kamo

I notice and document the way soft elements of the landscape have changed, there is less litter, fallen fruit is left on the ground. Fewer cars, fewer people. There is a sense of loss, a specific kind of aloneness on these walks, I take this time while my children are staying with their father. These walks are punctuated by the occasional police car, passers by, exchanging a glance or sharing greetings from a safe social distance. People queue for the local dairy, the roads are so empty.

Hot chips

Each walk is different, forming a new narrative, as I observe details and sometimes collect plants. As new streets and neighbourhoods become familiar, a feeling of connection expands outwards; this is another long distance relationship, like that with my partner, family and friends under lockdown.

Historic Bridge

It is on these walks, that I feel my connection to my place, here in Aotearoa. Otherwise, my sense of place and connection is lost in my day to day responsibilities and activities. These long walks refocus my attention to the place I am and when I am, the expansiveness of the outdoors contrasts starkly with the immediacy of domestic life with children and working from home.

Kamo

This project has enabled me to become more embedded in the city I live in. Janet Cardiff uses storytelling on her audio walks, where she invites a listener-walker to become intimate with the places she takes them. Likewise, with images and text, I have invited my Instagram community to walk with me in Whangarei.

King protea

Hearing from friends and family living in other forms of lockdown outside Aotearoa, walking outdoors is a cherished and legitimate activity, when almost all other movements are not allowed.

Lost highway

-

Time on her hands

We were in the back garden and I was helping to bring in the washing, I thought Nana was always so good with her washing, drying it on the line and a whizz at stain removal. Though, my mum seemed to believe she did laundry whether it needed doing or not. Implying that Nana may have slipped over the edge, that is she had become obsessive about doing the washing. What I remember is, if it was washing day, one did washing. The beds were stripped, towels and sheets were separated and the job got done.

At Nana’s it seemed like it was washing day every day. She even ironed her pillowcases and bras. However, to Mum, this was apparently a step too far, and an indication of having a little too much time on her hands. I thought it was, perhaps, one of the least concerning activities one could engage in, in such a predicament.

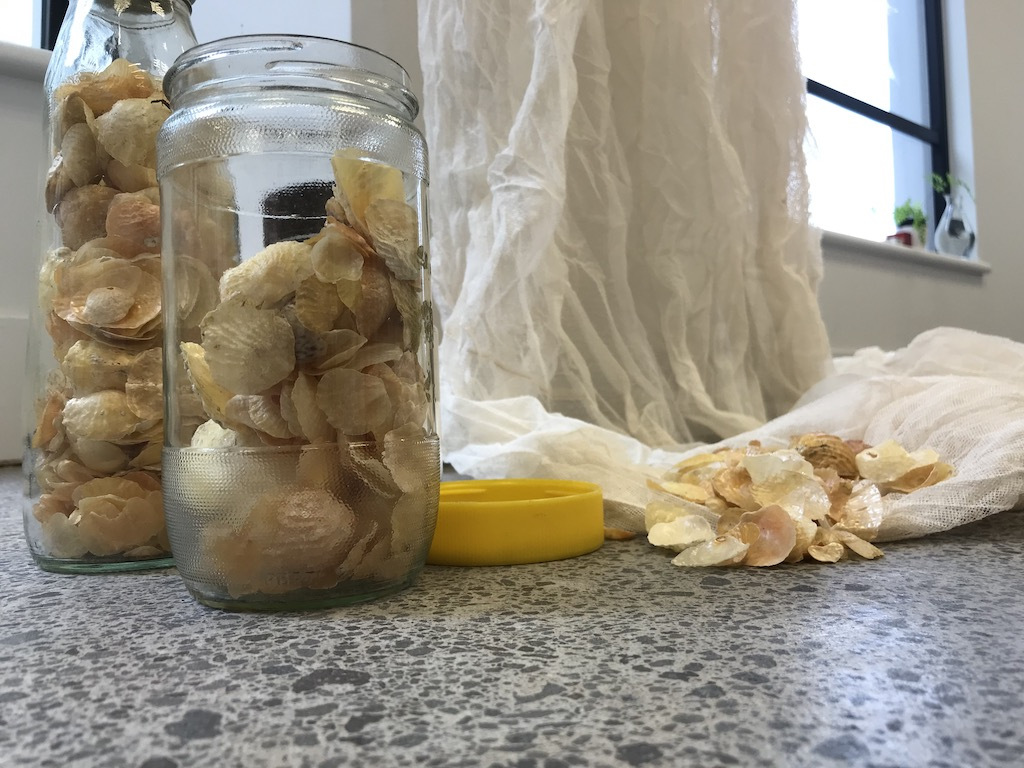

Part of the process of washing involved checking garments and household linen for wear, looking for holes or split seams. If any were found, the items were set aside, after being washed, to be placed in the mending pile next to her sewing machine. There were two kinds of mending; work to be done by machine, and that which needed more specialist attention, hand repair or darning. Most of the repair work was done by hand, with a limited range of stitches, which nonetheless extended the life and use of the garments, the tea towels, or the hankies (Fig.2.).

At the washing line, we tossed the clean laundry into the basket, pegs into the wooden holder; the washing was to be sorted and folded later, I don’t know where Nana did this, probably in the washhouse. These days, I sort and fold all my washing outside as it comes off the line, making piles in the washing basket. One for myself, one for each of my children and then the general household linen, such as towels, sheets, and cleaning cloths, all get folded and placed on the chair under the washing line. This feels like ‘High Level Efficiency’, the folded clothes can go straight into the drawers, the linen in the hot water cupboard. It avoids piles of clean laundry on the couch or my bed, the evidence of all the washing, gone.

I have admired clean washing piles in my friends’ homes, their sheets and towels take on interesting sculptural forms as they await the next step in the process. The work of ‘The Washing’ taking up living space, inviting folding, or just moving to another piece of furniture when someone turns up. The sheets are traces of intimate places and times, where one sleeps, has sex, dreams, rests, hopefully, at the end of the day. The piles of clean washing are a physical reminder of caring for a household. I think that is potential downside of ‘High Level Efficiency’, the work and time is rendered invisible, it has all been taken care of, no pause in the process.

Joy Smith, detail of repaired hanky. n.d. (Photograph by Angela Rowe).

-

I used to find dead insects in your pockets

I used to find dead insects in your pockets

I used to find dead insects in your pockets functions as an archive in flux, by attempting to make the absent visible or the lost tangible. Sue Breakell describes the fluid nature of working with an archive as having no “fixed meaning … we may know the action that created the trace, but its present and future meanings can never be fixed.”1. By choosing what to emphasise and what remains concealed, I seek to add further layers of meaning by re-contextualising these objects. I may manipulate them and so disrupt familiar associations, alternatively I may reproduce and repeat, the object then becomes the formal representation of a relationship; a social object.

These social objects allow me to figure out my relationships; I find ceramic fragments and mangrove seeds in the bottom of the washing machine when removing a load of my children’s clothes. Objects discovered and kept carefully in pockets, collected, valued and also forgotten. Relationships, traces of care and attention are entangled and mirrored in objects. Shells collected with Nana, or was it my friend or with my daughter? The objects resist conventional classification or containment. The process of working with these objects maybe what re-establishes intimacy and connection, as distances are crossed, memories slip in time and place. New modes of connection are added to the old and bonds are strengthened or left to slip away. It is the traces of ‘this life together’ which remain in the objects I have installed.

Fetish-like, these objects potentially offer up the spirit or trace of a relationship (debris) from a moment or place. Performing as prompts for memories, Marie Shannon notes that “ordinary objects can be very powerful”2 The everyday object is embedded in daily life, the small rituals we participate in most often. Stories are told and retold about the shells, the hair, skinks, seeds, et cetera. The blanket, folded and unfolded appears to be at rest, leaving traces of careful hands folding neatly and putting to one side. Storing the objects and living plants in jars evokes intentions of care, collection, and preservation. Living ferns and empty shells share space, resisting formal containment and classification.

Physicist David Bohm believed that shared meaning created through dialogue exchanged is the ‘glue’ that holds us all (people and society) together, allowing bonds to form over time.3 Working with my extended community so as to create an archive of objects becomes a kind of social practice and a way to work out and understand relationships, ‘meaning making’ and ‘sharing meaning’ in the form of a dialogical exchange that Bohm describes.4 This time the exchange and sharing happens between object and person, then person and person, and again between person and object. It is this kind of connection and exchange that has informed my practice, permitting many different forms across time and place, as seen when sewing Nana’s net curtains. It may result in many traces in the form of objects, as objects can hold meaning and significance across generation and place. In particular, I am working with my Nana, my children and my intimate circle of friends, as we exchange a type of care dialogue.

Please use the jug to water the ferns, if they are looking dry.

Notes:

1 Breakell, Perspectives.

2 Monsalve, The Art of Domestic Life

3 Bohm, On Dialogue.

4 Ibid.

I used to find dead insects in your pockets

List of works:

Golden Oyster, not a true oyster, golden oyster shells, brachiopods, cats eye shells, cockle shells, unidentified seeds, feathers, cicada skins, green jewel beetle, dragonfly, white cabbage butterfly, cicada, moth, monarch butterfly, kauri gum, kauri cones, bird bones, pink clay pebbles, Ron’s hair, Angela’s hair, fishing nylon, oil paints, ceramic fragments, unidentified rocks and fragments, wishes, sea urchins, sea stars, kina, coral, aquarium pebbles, marbles, glass fragments, dust, sea weed, sea sponges, preserved algae, skinks, salt crystals, fossil trilobites, clover buds, kauri snail shell, paper wasp nests, matchbox truck wheels, mermaids purses, paua shells, limpet shells, empty birds eggs, sea dollars, plastic ballerina, wentletrap shell, kelp holdfast, fan shells, sand, purple sunset shells, dried leaves, silver dollar seeds, crab back, cocktail umbrella, sea glass and box of rocks and wooden print blocks.

On the smallness of things, Angela’s maidenhair fern, Fränzi’s maidenhair fern, Jeremy’s maidenhair fern, Jodie’s maidenhair fern, Mum’s maidenhair fern, Luna’s maidenhair fern, Ron’s maidenhair fern, begonia, asparagus fern, monstera, and water weeds from Whau Valley Dam.

Keep care, nylon net curtains, dyed with avocado pits and skins, taffeta curtains.

Time on her hands, orange curtain off-cuts, embroidery thread.

Catch stitch, Nana Joy’s blanket, Angela’s blanket.

-

what remains – group exhibition DEMO 13 – 15th June 2019

Two works installed in the group show, what remains at DEMO as part of the DEMO Season 2019.

I say a little prayer for you; gathering material. Found textile, lipstick, mascara, foundation. Dimensions: 3m x 2m x 1m, frame 1.7mw x 3.2mh.

Exhibition text:

Angela Rowe’s work involves a community of women making imprints of their face in make-up to address the societal constructs of beauty, identity and gender. She aims to draw out stories and connections between women through shared ritual and performance.

I say a little prayer for you; gathering material, quilt was installed on a timber frame.

Cloth books

I say a little prayer for you; the hours. Found textile, lipstick, mascara, foundation. Dimensions: Variable, table, books 45cm x 35cm

what remains birds eye view.

Thanks to Victoria Hollings for curating and organising the show and the other artists and helpers, thanks Noel for making the frame.

This is part of an ongoing project, I say a little prayer for you.

-

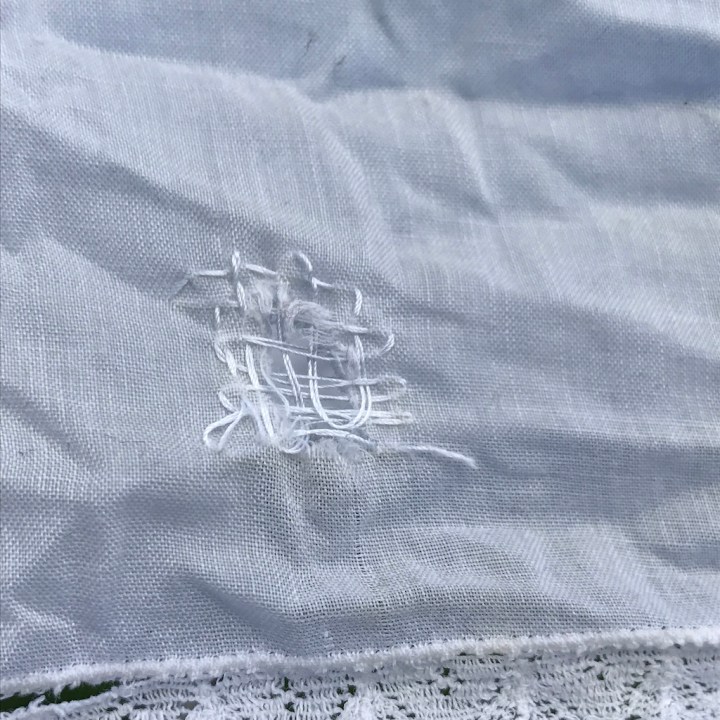

I say a little prayer for you

Using a process of conversation, listening and recording, I collect stories and produce objects which help me understand relationships, my research method also happens to be collaborative. This process is durational, both in the exchange of ideas and stories and how I chose to contextualise and re-perform the material. In I say a little prayer for you, this includes retelling stories, live in public spaces and live to air in the form of radio broadcast.

The collaborative component in I say a little prayer for you happens in domestic, private spaces, within a framework of trust, it takes time and care. The context for the work includes modes of sharing and collaborating which have historical connections to how women come together and form community.

Is it possible to represent the nuanced and contradictory individual stories shared with me, and is the work interpreted as a display of collective experiences of women? My response to this challenge has been to present the self portraits as physically connected works, in a quilt or cloth books and sharing women’s sometimes contradictory reflections. This is an attempt to avoid reducing the work into a universal homogenous response and to draw attention to the stories which came from the process, these stories seem to be the heart of the work.

Joanna S. Walker highlighted the absence of the body of the artist or performer; the trace of the work or a performance was ephemeral or suggestive of other ways of seeing.1 Making a shift from ‘seeing’ to ‘hearing’ I attempt to shift focus from the formal outcomes of my process. The self portraits, and my reworking of them into quilts, cloth books and embroideries, is a way for me to understand the research and reconnect with my collaborators.

As I develop this project further, I aim to highlight a discourse between the differing experiences women shared in response to the project. I continue to collect traces of actions in the form of self portraits and their experiences in the written stories they shared with me.

By bringing stitch into my process, these ideas are carried further, the relationships are then embedded in the work. Expanding the process from an intimate collaboration to re-telling these stories live on air as a podcast, the work may become more expansive, and the performance is on going. The singular moments from women’s lives then expand outwardly via the radio broadcast.

You can listen in to this podcast here;

Beagle radio I say a little prayer for you

Notes

[1] Walker, Joanna S. ‘The Body Is Present Even If in Disguise: Tracing the Trace in the Artwork of Nancy Spero and Ana Mendieta’. Accessed 12 August 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/11/the-body-is-present-even-if-in-disguise-tracing-the-trace-in-the-artwork-of-nancy-spero-and-ana-mendieta.

-

I say a little prayer for you; good results are difficult when indifference predominates

MFA Summer seminar installation and video fragments.

Statement text:

I say a little prayer for you; good results are difficult when indifference predominates

Never approach sewing with a sigh or lackadaisical attitude. Good results are difficult when indifference predominates. Never try to sew with the sink full of dishes or bed unmade. When there are urgent housekeeping chores, do these first so that your mind is free to enjoy your sewing.

When you sew, make yourself as attractive as possible. Go through a beauty ritual of orderliness. Have on a clean dress. Be sure your hands are clean, finger nails smooth — a nail file and pumice will help. Always avoid hangnails. Keep a little bag full of French chalk near your sewing machine where you can pick it up and dust your fingers at intervals. This not only absorbs the moisture on your fingers, but helps to keep your work clean. Have your hair in order, power and lipstick put on with care. Looking attractive is a very important part of sewing, because if you are making something for yourself, you will try it on at intervals in front of your mirror, and you can hope for better results when you look your best. If you are constantly fearful that a visitor will drop in or your husband will come home and you will not look neatly put together, you will not enjoy your sewing as you should.

Mary Brooks Picken, Singer Sewing Book, 1949.

I say a little prayer for you; good results are difficult when indifference predominates

Gathering material

Collected self portraits; found textile, sheets, mascara, lipstick, foundation.

Invitation to participate.

Correspondence

Plastic bag, envelopes, text from correspondents, performance.

Reading, Wednesday 23 January, 2019, performance commencing 6.45pm.

Good results are difficult when indifference predominates

Durational performance, Saturday 19 January, 2019, commencing 11.15am.

Performance images, thanks to Victoria Hollings.

-

Everyone’s a stranger to me now

Everyone’s a stranger to me now, detail of pressed work

About the exhibition:

I can’t put my finger on it brings together artists that eschew object based or pictorial representations and embrace instead, an experience of materiality that is no longer a given or manifest trace of human agency. These works seek to challenge hierarchies of consciousness that objectify relationships, beings, language and materials and offers instead, a new materialism and means of knowing the world beyond ‘thingness’.

Opening at 6pm on Thursday, November 1st. Sponsored by Epic Beer!

Everyone’s a stranger to me now, performance in ‘I can’t put my finger on it’, a group exhibition at DEMO, 1 – 4 November 2018.

Everyone’s a stranger to me now, wall work

Everyone’s a stranger to me now is a durational performance; pressing, steaming, sizzling as moisture is forced from pieces of cloth which hold images that suggest the face, the trace of a woman, a moment that has passed.

A fraction of my performance, Everyone’s a stranger to me now, for the opening of

I can’t put my finger on it, a group exhibition at DEMO, 1 – 4 November 2018.

The work of ironing; pressing, carefully, slowly, mirrors work of care, attention and process, the cloth changes from damp grey material to a crisp, dry, white, cloth but still stained, and progressively may burn. The process of ironing is never complete, the creases never really leave, returning with use and laundering.

The imagery on the cloth may suggest the face, a smear of mascara, stained and smudged by another movement, pressing, rubbing, removing.

Thanks Victoria Hollings for the photos and video of the performance !

This post was originally published on my student blog, here.

artist, writer, curator, mentor